By Ilene MacDonald |

ORLANDO, Florida—When the first CVS retail clinic opened 16 years ago in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, it was meant to be an affordable option for patients who needed care for strep throat or a sinus infection when their primary care provider’s office was closed and they didn’t want to go to the local emergency room.

It has since morphed into a competitive model that offers acute care services, preventive care, health condition monitoring and wellness programs seven days a week, evenings and weekends. There are now more than 2,300 retail health clinics in 43 states, and the industry expects that number to double in the next five years. CVS is the largest of those retail providers and operates 1,100 of those clinics in 33 states and the District of Columbia.

And though some providers view may retail clinics as a threat, “we see ourselves as a safety net for primary care,” Angela Patterson, chief nurse practitioner officer, MinuteClinic and vice president, CVS Health, told attendees at a session during the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s 28th annual National Forum on Quality Improvement in Healthcare in Orlando, Florida.

Model based on convenient, affordable care

“We are that point in between the primary care provider and the higher acuity level of care in our community. We see ourselves as the access point when the patient can’t see their PCP because they are traveling or can’t get an appointment or for the medically homeless,” she said.

Retail health’s growth in the industry centers on its ability to provide convenient, affordable access to care. Indeed, 52 percent of Americans now live within a 10-mile radius of a MinuteClinic. Patterson said the locations, as well as its affiliations with more than 70 health systems—including the Cleveland Clinic and Rush University Medical Center—allow CVS to support population health initiatives at the local level.

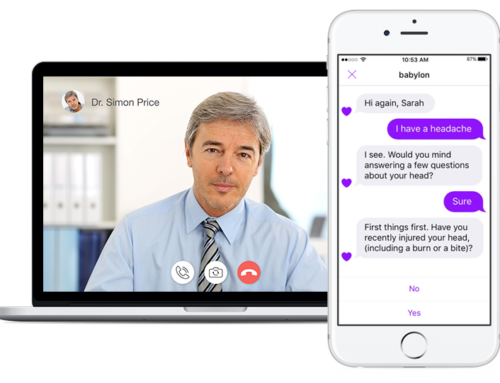

And the retailer continues to evolve the model to meet the needs of its patients. One pilot program in California and Texas is experimenting with adding telehealth to the existing MinuteClinic model to expand the retail health clinic’s access to care in areas that have clinician shortages. Those retail health clinics are staffed with nurses, who then communicate with nurse practitioners in another part of the state. The addition of telehealth is promising, Patterson said, noting that the clinics had 20,000 visits through the method and 95% of patients reported that telehealth was just as good—if not better—than a traditional visit. Furthermore, a third of those patients said it was better than an in-person visit.

CVS is also working on initiatives to improve population health, such as antibiotic stewardship, health literacy, healthcare interoperability, chronic disease management, immunizations, smoking cessation and weight-reduction programs.

“We certainly see a tremendous opportunity to grow and advance practice,” she said. “Our strategy is in partnerships supporting aims and goals in health in conjunction with other organizations.”

Model’s biggest challenge: Provider satisfaction

But like other healthcare organizations, retail health also struggles with workforce retention. While patients appreciate the convenience of access to care every day and night of the week, nurse practitioners don’t enjoy giving up their evenings, weekends and holidays.

“The hours aren’t for everybody,” Patterson admitted. “We have to be there Friday, Saturday, Sunday and Monday and that’s really hard for providers who also have families and are caring for their parents. The weekend thing can be a deal breaker and it’s really challenging, even though we want them to stay with us and grow professionally.”